|

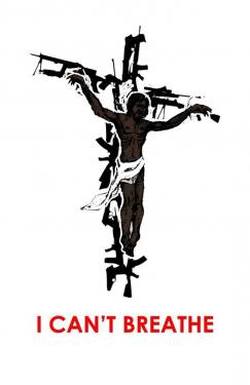

By: Gregory Williams This piece is, in many ways, an attempt to pick up a conversation that I tried to start two years ago, in 2013, when, New England, the region where I lived and worked, was responding to two violent events which received a great deal of media attention: the Newtown school shooting of December 14, 2012, and the Boston marathon bombing of April 15, 2013. It was a difficult conversation, then, and it is a difficult conversation now. To be right up front about it, dear reader, I am writing to tell you not to publicly mourn the death of a police officer. If you don’t want to read that kind of essay, now is the time to stop reading this one.  WHITE MARTYRDOM AFTER NEWTOWN AND BOSTON I wrote Newtown, Boston, and the Martyrology of Whiteness after it seemed as though New England had been in continuous mourning for several months. In December, 20 children and 6 staff at the Sandy Hook Elementary school had been killed, and faces of the victims, particularly white victims, were appearing on television screens and social media. Then, in April, three people were killed and hundreds were injured after a bomb exploded during the Boston marathon. The pictures of the victims were not as prominent in the media coverage, but what was was the non-white racial identity of the alleged killers. As someone working, at that time, with people who were undocumented, incarcerated, or homeless, most of whom were people of color, I could be (perhaps cynically) unfazed by the volume of mainstream and social media coverage: the deaths of children do not garner as much attention if those children are not white. What shocked me was the very personal nature of the treatment that the suffering that occurred at Newtown and Boston was receiving. I wrote, at the time, We are going beyond saying that the Newtown school shooting and the Boston marathon bombing are traumas--which they are—to the point of saying that they are our traumas. Facebook memes are abounding encouraging people to hug their kids or drop f-bombs about the levels of evil in the world and the like—things that one would normally do not to sympathize with another person but rather to express grief for one’s own loss. In Church, we are singing songs like “I Want Jesus to Walk with me” and “How Can I Keep from Singing?” songs that express a personal sense of grief and loss. I put forward three specific propositions in my essay:

White martyrdom is extremely dangerous because it touches on the deepest personal, emotional, and spiritual parts of the psyche and manipulates people into investing in white might be called the cult of whiteness, or the theology of white inviolability. What this means, in a nutshell, is that public prayer, commemoration, and lamentation after a traumatic or violent event is never politically neutral, but demands an investment in particular value judgments, value judgements that are always, always racialized. There is no such thing as a moment when it is possible to “stop all the politics and just pray” - indeed, it is calls for such moments that add a unique, pernicious potency to the martyrology of whiteness. When churches and other faith communities held public liturgies of lament after Newtown and Boston, these functioned as rallies for whiteness - indeed, for white supremacy. These claims shocked many people at the time - indeed, I was afraid to make them myself. It is generally considered bad form to criticize other people’s public prayers - which is problematic because prayer is still a kind of public discourse. Moreover, it is considered highly inappropriate to look at someone’s mourning or lamentation and find any fault with it - much less call it out as white supremacy. But this is exactly what was needed at that time - and now I strongly feel that this analysis is relevant once again, as people gather to venerate another martyr to whiteness, Brian Moore of the New York Police Department. COLLECTIVE TRAUMA On the evening of Saturday, May 2, 2015, Brian Moore, a white officer of the New York Police Department was hospitalized with a gunshot wound to the head. Two days later, he died.1 Almost instantly, state and civil society groups began to publicly mourn his death. New York City and State flags were flown at half-mast until Moore was buried on Friday, May 8. And all over Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumbler, and other social media sites, christians – especially christian pastors, seminarians, and other public leaders – are posting their prayers and best wishes for New York and for the NYPD. Most tellingly, the New York Mets observed a moment of silence during their game against the Baltimore Orioles on Tuesday, May 5, 2015 and wore NYPD caps during batting practice. This is an enormous contrast with the response of the Mets’ rivals to the violence directed against women and men of color in their town. Even while, after his grandfather’s store was damaged during the Baltimore insurrection, the Orioles’ COO, John Angelos, spoke out, identifying poverty and joblessness as among the real issues, he still called for “the rule of law” (a classical trope used by public figures to put down black militancy from the civil rights era to the present).2 Moreover, Baltimore baseball fans still watched as their team observed a moment of silence for a dead police officer, while no such official commemoration was given to Freddie Gray. The message of all of this is clear: the death of a police officer is a “public trauma” in a way that the death of an unarmed civilian of color at the hands of police simply is not. Everyone - even those currently struggling against the structural racism of police terror - is expected to be in mourning when a police officer dies and is treated accordingly in public discourse. Public prayer, public commemoration, public lamentation of any kind - even and especially when it is done by christian leaders - helps to build this expectation. NORMATIVE WHITENESS As a police officer, Brian Moore is a representative of the white supremacist power structure, and he would be, even if he were not white himself. However, the ongoing public commemoration of his death is taking full advantage of the fact that he was white in order to construct him as a martyr to whiteness. One need only scan the media coverage to see Moore remembered as “selfless,” “diligent,” “dutiful,” “courageous,” and with other positive qualities which white police officers are supposed to have. This positive commemoration, this setting up of Moore as an example of public virtue (a consequence of his death’s construction as a public trauma), is inseparable from his construction as a martyr to whiteness. Unlike Trayvon Martin, no one asked what Brian Moore was wearing, or whether that might make him look like a violent criminal and a potential threat to peaceful civilians. Unlike Michael Brown, no one asked why Brian Moore was in that street, and whether his presence there could have been seen as threatening. Unlike Eric Garner, no one threatened, harassed, or arrested those who testified to Brian Moore’s virtue, or the innocence of his suffering, during the investigation of his death. Unlike Freddie Gray, no one asked whether Brian Moore was armed, and whether this may have contributed to his being perceived as “a threat to my life” by the man who killed him. Finally, unlike all four of these black men, and so many more women and men of color throughout this country who are dying at the hands of police and security officers every twenty eight hours, no one asked whether it was appropriate to file first-degree-murder charges against Brian Moore’s alleged killer. To be blunt, some of these are far more intelligent questions to ask of an on-duty police officer than any of the civilians of color that police have lynched in recent years. WHITE MARTYRS, WHITE POWER If one needs any further proof is needed of the way that police officers’ deaths are constructed as martyrdoms to whiteness, all that is required is to look at the way that the rhetoric around police killings has been ramped up in the last few months as the #BlackLivesMatter movement has taken off in the wake of the Ferguson insurrection. One of the first responses from the forces of white supremacy was the circulation of the slogan (and competing twitter hashtag) “Blue Lives Matter” - that is, police officers’ lives matter. This slogan is an extension of the argument that almost every police officer makes to justify lynching a black or brown civilian: “I feared for my life.” The message is clear: “if you think that black lives matter, you should remember that the women and men of color you are defending died because they threatened the lives of police officers - because they were dangerous criminals more generally - and police officers die protecting the (normatively white) public against them, and police lives matter.” The danger faced by police officers working in black and brown communities is directed invoked over and against the danger faced by civilians in black and brown communities at the hands of police. “Black Lives Matter” is answered with “Blue Lives Matter.” The logic of public commemoration of police officers is the logic of a noble white public servants facing off against dangerous black criminals. It is the ideology of white supremacy veiled in tears, in moments of silence, and in public prayer. Patrick Lynch, the President of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, made this logic explicit when he called Brian Moore “another brave police officer who placed his life between crime and the good people of the city.”3 This dichotomy between “crime” and “good people” is thinly hidden language for the dichotomy between black and white that is fundamental to the legal, political, economic, and social logic of this country, with Moore positioned squarely in the middle, as the blue life that matters over and against the criminal black and brown lives that don’t. STOP LAMENTING: THE DIFFICULT REFUSAL OF WHITE PATRIOTISM When I first wrote Martyrology of Whiteness for Jesus Radicals, I was much more hesitant than I am about writing a redux of that piece today. Perhaps, I was wiser and more humble then than I am now. Then again, perhaps I have simply lost patience after seeing, too many times, the ways in which public lamentation, including the public lamentation of christian churches, functions to reinforce white privilege and white supremacy in public discourse in this country. Again, perhaps I am just too angry already from months of negotiating public responses from white christians to the murders of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Freddie Gray, and to the public police beating of Teandrea Cornelius and the recent anniversary of the murder of Malik Jones in my own city, and I just can’t take any more. No matter what the reason, I am going to end this piece in a way that I would never have dreamed of closing my previous essay: I am going to give a concrete suggestion. Please stop publicly praying for, commemorating, and lamenting the death of Brian Moore. Please do not post anything about him on facebook. Do not include him in the prayers of the faithful at your church. Do not go to a vigil for him. Do not observe a moment of silence for him. To do so is an act of white supremacy. This appeal may seem drastic, but I hope, from the above analysis, that you, dear reader, can tell why I am making it. In a world where some people are treated as martyrs to whiteness, and other people are treated as though their lives do not matter, it is impossible to publicly commemorate the deaths of the martyrs to whiteness without venerating whiteness itself, just as surely as it was impossible, under the Roman Empire, to commemorate a martyr to Christ without implicating oneself in the Christian message. I do not say this to devalue Brian Moore’s life. I do not mean to reduce anyone’s empathy for him, or for any other human being for that matter. Were this my message, I would not be proclaiming the gospel of the God who causes sun to shine on the righteous and the unrighteous alike (Matthew 5:45) and who calls God’s people to do good to all and honor everyone (1 Peter 2:17). But this kind of charity can be practiced just as easily in a way where one’s left hand does not know what one’s right hand is doing (Matthew 6:3). Public commemorations are something different. They help to give a “plot” to the story of a person’s life and death, and the story that Brian Moore was “another brave police officer who placed his life between crime and the good people of the city” is not an acceptable narrative for anyone committed to anti-racist praxis. Even more importantly, even and especially in the midst of public commemorations for police officers and repetitions of slogans like “blue lives matter,” we must stand firm, continue in the struggle, and remain committed to building a broad-based, organized, militant, insurrectionary social movement against police, prisons, borders, and every other violent, racialized mechanism of apartheid and social control in this country. We must stay in the streets and on the picket lines to shut this whole damned system down. We must continue to write, to theorize, to speak, to organize, to agitate, to make art and poetry, to defend one another from this terrorist police state, for this is our spiritual worship, our living prayer for God’s reign come and will done on earth as in heaven. Comrades in the struggle for a new heaven and a new earth, let us march onward together! Notes:

Comments

|

Disclaimer

The viewpoints expressed in each reader-submitted article are the authors own, and not an “official Jesus Radicals” position. For more on our editorial policies, visit our submissions page. If you want to contact an author or you have questions, suggestions, or concerns, please contact us. CategoriesAll Accountability Advent Anarchism Animal Liberation Anthropocentrism Appropriation Biblical Exegesis Book Reviews Bread Capitalism Catholic Worker Christmas Civilization Community Complicity Confessing Cultural Hegemony Decolonization Direct Action Easter Economics Feminism Heteropatriarchy Immigration Imperialism Intersectionality Jesus Justice Lent Liberation Theology Love Mutual Liberation Nation-state Nonviolence Occupy Othering Pacifisim Peace Pedagogies Of Liberation Police Privilege Property Queer Racism Resistance Resurrection Sexuality Solidarity Speciesism Spiritual Practices Technology Temptation Veganism Violence War What We're Reading On . . . White Supremacy Zionism ContributorsNekeisha Alayna Alexis

Amaryah Armstrong Autumn Brown HH Brownsmith Jarrod Cochran Chelsea Collonge Keith Hebden Ric Hudgens Liza Minno Bloom Jocelyn Perry Eda Ruhiye Uca Joanna Shenk Nichola Torbett Mark VanSteenwyk Gregory Williams Archives

October 2017

|

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed