|

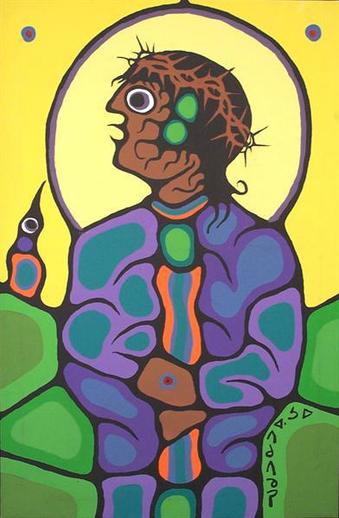

8/25/2016 Comments A Blog Commentary on Luke's Gospel, Written for Settlers in the Occupied Territories Called Canada (Part, 1)By: Dan Oudshoorn  Painting by ᐅᓵᐚᐱᐦᑯᐱᓀᐦᓯ. Painting by ᐅᓵᐚᐱᐦᑯᐱᓀᐦᓯ. Note: Originally published on Dan's blog, On Journeying with Those in Exile Jesus was an Indian. If you don’t understand that, you won’t understand any of the rest of it, so you’ve got to get this first. Let me try to be clear about this. By saying that “Jesus was an Indian,” I don’t mean that Jesus was from India. India didn’t even exist back in his day, given that what we call India was actually a number of different kingdoms or empires rooted in people like the Satavahanas, or the Indo-Scythian Sakas, or the Mahameghavahanas, to name just three of about a dozen different options. So I’m not saying Jesus was a proto-Indian, as though he came from that region. Furthermore, although a fringe group of people like to say Jesus went to India to study and learn in the years we hear nothing about in the canonical Gospels (for example, in an universally discredited book claiming to offer “irrefutable evidence” and entitled Jesus Lived in India, Holger Kersten argues Jesus lived in India when he was young, where he became a spiritual master in Buddhism, and then returned there to grow old and die after he rose from the dead), that’s not what I’m saying. No, Jesus was an Indian in the same sense that the Haudenosaunee, the Anishinaabeg, the ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐤ, the Wet’suwet’en, the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, the Tlicho, and the more than 630 First Nations in Canada are Indians. And Jesus is an Indian in exactly the same way that members of all of these nations are Indians. Because what does it mean to say that the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island are “Indians”? Well, to begin with, it means that they are a people who have been colonized by a foreign power who gives them names not of their choosing. This applies as much to people as it does to the land. Hence, Turtle Island is no longer known as Turtle Island. It is called North America, and Canada, and the United States of America are the nations that are said to be present there (I’ll stick to Canada in what follows, as that is the land my people have colonized). And in Canada, for most of its history, the original peoples – the Onkwehonwe to use the Kanien’kehá:ka word – were not known by the names they had received from the land but by the names given by those who colonized both them and the land (although it is wrong to imply that the people and land can be separated and thought of as two distinct entities). They became Indians because that was the name given to them by the settlers who wielded power over Life and Death and who gave out the latter far more than the former.

Comments

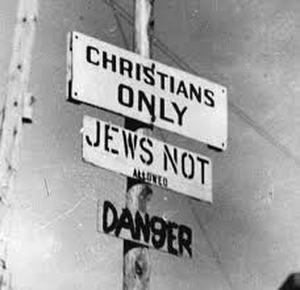

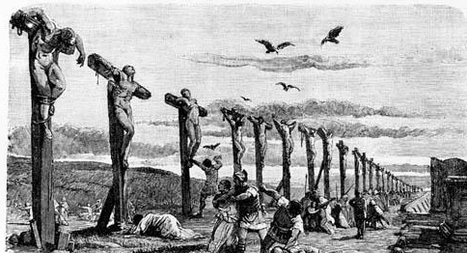

11/8/2015 Comments Is Eating Animals An Act of Love?By: Kyle Sumner  According to traditional Christian thought, the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus lays out a framework of sacrificial love for both God and neighbor. The Gospels of the New Testament are centered on the idea of a God who forsook Heaven to dwell among and restore a fallen creation. Rather than using power to rule in a top-down fashion, God took the form of a servant and chose to embrace the brokenness of the world. Biblical restoration, in essence, starts from the bottom up. This view of the biblical narrative supports a theology of liberation that has influenced black, feminist, womanist, and queer theologies in recent history. This view of a Messiah who stands in solidarity with the oppressed and marginalized has provided a foundation for many human rights campaigns and social justice issues, but many theologians who claim to be motivated by a God of liberation have largely glazed over issues of animal exploitation. This lack of concern for the non-human animal world has caused me to ask quite a few questions: Are animals to be considered fellow Creatures deserving of respect? Does a faith that is rooted in the life and teachings of Jesus demand of us a new way of living in relation to non-human animals? Is it possible for one to consider ones self on the side of the oppressed if they consume the flesh of those they seek to liberate? In order to answer these questions we must first look at Jesus’ unique relationship with food. 4/14/2015 Comments Supersessionism, Jewish Whiteness, and Liberating Biblical Study in Post-Ferguson AmericaBy: Gregory Williams GregWilliams  “Well, the text seems to say that Christianity supersedes Judaism.” I gasped, as did everyone else in the area. Not only could I not believe that I was hearing these words, but I couldn’t believe who the speaker was, either. The context was my New Testament exegesis seminar on the Epistle to the Hebrews and the speaker was my friend, Jeremy. Jeremy (a black Methodist pastor) and I (an Ashkenazi Jewish Christian) had become friends during the past two years and were, in particular, allies in predominantly liberal white protestant classrooms where we endeavored, together, to raise issues of poverty, slavery, empire, and anti-Semitism in biblical texts and historic Christian theologies, constantly pushing our professors with our “resistant readings.” In this particular class, we had been at this for the better part of a semester, and our efforts had included a thoroughgoing critique of supersessionism, the idea that the New Testament community sought to found a new religion, Christianity, which they conceived of as superior and a natural successor to the “old covenant” of Judaism. Thus, I was shocked when I heard him endorse the idea in class. “I wanted to test a theory,” he explained to me later. “You see, as a white Jew, every time you talk about supersessionism, no matter how much you are challenging our professor or our colleagues’ ‘traditional’ scriptural interpretations or theologies, you are listened to with respect. But whenever we try to talk about slavery, or genocide, or colonialism—well, let’s just say that the mention of any of these realities wouldn’t get the kind of gasp that my pretending for a moment to endorse supersessionism got. Now, I know that you want to critique absolutely everything, but doesn’t it bother you that white Jews always seem to be first in line to have their grievances heard in New Testament studies?” It didn’t take me long to realize that Jeremy was right. As a Jew, I interpret the Bible from the standpoint of a subaltern ethno-religious community that experienced more than a thousand years of geographic displacement, economic exclusion, cultural segregation, and, in the last century, genocide. As a white person, however, I experience the privilege of having my resistant readings of scripture always come first in line, often ahead of black and brown voices who speak from a subaltern community that experiences displacement, impoverishment, segregation, and violence right now, even as many Jews, including myself, are accorded white privilege in the twenty first century construction of race in America. By: Drew Hart Note: This article originally appeared on The Christian Century  As we reflect on what we so casually refer to as Good Friday, we are called to remember and reflect on the significance of Jesus’ death, which itself has a contested meaning in the Church. Some of the challenges around the meaning of Jesus’ death is related to the way his death is divorced from the narratives of his life. Jesus’ death is often placed in a context-free vacuum, in which it is only about our forgiveness of sins (carried out through divine contract). Such abstractions willfully choose to not read Jesus’ death in the context of his life. The political confrontation, the power-dynamics, the concerns of the masses, the subversive implications of the narrative’s plot, and the inherent judgment of Yahweh that came and judged the injustice and idolatry of the Jerusalem establishment which is echoed through the use of Israel’s prophetic texts, are all made invisible in the Jesus stories. All of this leads up to, and interprets, Jesus’ death. However, according to Luke’s narration, the earliest followers of Jesus understood his death as something done by the socio-political players of his day: “our chief priests and rulers handed him over to be condemned to death, and crucified him.” (Luke 24:20, NET) We are given even more in Acts when Peter summarizes Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection like this: 12/9/2012 Comments The Season of TearsBy: Gregory Williams  In the Church where I was baptized, I was taught that Advent was for those of us who are too depressed to do Christmas. Every year, for these four weeks, we were reminded that one of the spirit’s greatest gifts to a Christian community is that community’s ability to live with weakness, to admit its need for grace, to name the absence of God in our lives in the midst of a culture characterized by triumphalism and willful blindness to pain. One year the pastor demonstrated this quite dramatically in a sermon. “There are many Churches,” he said, “that, in order to accommodate those who mourn the loss of loved ones at Christmas or who cannot be with family for other reasons, hold a “blue Christmas” service.” He then held up his (blue) stole and exclaimed, “we don’t need to do that because we already have a blue Christmas. It’s called Advent!” While I have since moved away from this Church, I believe that its emphasis on periods of mourning and lamentation has political significance, particularly for those of us who integrate anarchist praxis into our path of discipleship. One of the major defensive mechanisms of Imperial Religion is its ability to rob us of our tears. We live amidst an interlocking set of globe-spanning political, social and cultural systems founded upon the colonial dispossession of land and displacement of people, particularly low income people and people of color, making room for the capitalist transfiguration of every person place and thing into a commodity to be marketed, used and thrown away. Our life together in creation is also marred by the heteropatriarchal scripting of gender and sexuality that rests on oppressive dualisms of culture and creation, rationality and affect, mind/spirit and body and male and female. This social system is responsible for the deaths of millions, for historic and ongoing genocide and for the near-constant burning of the bodies of children, women and men upon the fiery altars of imperial war.

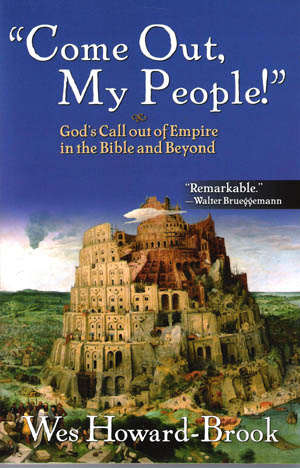

In Tell Us Our Names: Story Theology from an Asian Perspective, C.S. Song turns on its head pre-Communist era missionaries’ complaints against some Chinese converts being more interested in feeding their stomachs than their souls. The hungry suspects were accused of being “rice Christians”. He writes that, “we celebrate Christ’s divine presence in the eucharist… [because] in Christ the divine future,” a Kin-dom of God wherein all stomachs will be fed, “becomes the human present.” He writes of the hungry suspects: Rice determined their present and their future. Rice brings a concrete content to all talk about the future, about the world to come, and about the kingdom of God. For those who subsist on rice, can there be a future without rice? Can there be a world to come where they must struggle again for rice? . . . Understanding rice in this way, Christians in China should have been proud to be “rice Christians.” They should have represented this kind of “rice Christianity” to their rice-hungry compatriots. Preachers should have preached “rice sermons” to their famished audiences… theology must serve the God of the present- a God whose pockets are full of rice.1 By: Frank Cordaro  I have wanted to read this book for many years. It just was not written yet. Now that it is, we Catholic Workers and faith-based-nonviolent-resistance-to-the-USA-Empire type folks owe Wes Howard-Brook a debt of gratitude. Not since reading Ched Myers’s ground-breaking Binding the Strong Man has a book so influenced my reading of the scriptures. What Myers did with the Gospel of Mark, Howard-Brook does for the whole Bible by laying out a template for reading it. Come Out, My People! addresses two major issues that have plagued my reading of the Bible. The first is the seeming great divide between the New and Old Testaments, or what we Christians have called our “Jewish question.” James Carroll’s book Constantine’s Sword, documents this tragic misreading of the scriptures and the bloody history that has followed. The current political discourse surrounding the State of Israel shows that these issues are still very much with us and not going away anytime soon, My second issue surrounds the question of violence in the Bible. Jack Nelson-Pallmeyer’s book Jesus Against Christianity highlights this perplexing issue well. Nelson-Pallmeyer asks the question, how are we who believe in the nonviolent Jesus and the unconditionally loving God of unlimited forgiveness with the violent deeds attributed to God and God’s people in the Bible? Nelson-Pallmeyer‘s answer is a bold and liberating one. If we really believe in that Jesus and that God, then where ever God is portrayed as violent in both the New and Old Testaments, the violence is human pathology imposed on the text. I find Nelson-Pallmeyer’s answer very appealing. It rings true in my spiritual guts. Yet it is somehow too convenient, too easy a solution. It does not adequately or systematically deal with the Bible’s violent biblical texts. By: Sarah Lynne Gershon  Recently I have been struggling with what the appropriate response to a Liberationist perspective within my context would be. At Missio Dei [now, the Mennonite Worker], Latin American Liberation theology has influenced a lot of our ideas about what the gospel really means, what Jesus calls us to, and what the Kingdom of God looks like. We’ve talked a lot about becoming family with the poor and marginalized in our context, about questioning the assumptions underlying the accumulation of wealth (embracing jubilee), and rejecting social structures that disempower. As we’ve talked about this, we’ve tried to reorient our lives and adopt practices that will conform us to God’s kingdom and the person of Jesus, but until recently I’m not sure I’ve understood what it means for me to do these things. There is always a tendency within me to believe that I am simply called to give what I have to the poor, to serve them, to somehow leverage my power in such a way to help the poor and marginalized among us. While I think we are called to those things, they are not at the heart of Liberation theology. As long as I reject the basic reorientation of perspective that Liberation theology calls me to, I am still reinforcing the same systems and social structures that dehumanize and disempower. |

Disclaimer

The viewpoints expressed in each reader-submitted article are the authors own, and not an “official Jesus Radicals” position. For more on our editorial policies, visit our submissions page. If you want to contact an author or you have questions, suggestions, or concerns, please contact us. CategoriesAll Accountability Advent Anarchism Animal Liberation Anthropocentrism Appropriation Biblical Exegesis Book Reviews Bread Capitalism Catholic Worker Christmas Civilization Community Complicity Confessing Cultural Hegemony Decolonization Direct Action Easter Economics Feminism Heteropatriarchy Immigration Imperialism Intersectionality Jesus Justice Lent Liberation Theology Love Mutual Liberation Nation-state Nonviolence Occupy Othering Pacifisim Peace Pedagogies Of Liberation Police Privilege Property Queer Racism Resistance Resurrection Sexuality Solidarity Speciesism Spiritual Practices Technology Temptation Veganism Violence War What We're Reading On . . . White Supremacy Zionism ContributorsNekeisha Alayna Alexis

Amaryah Armstrong Autumn Brown HH Brownsmith Jarrod Cochran Chelsea Collonge Keith Hebden Ric Hudgens Liza Minno Bloom Jocelyn Perry Eda Ruhiye Uca Joanna Shenk Nichola Torbett Mark VanSteenwyk Gregory Williams Archives

October 2017

|

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed