|

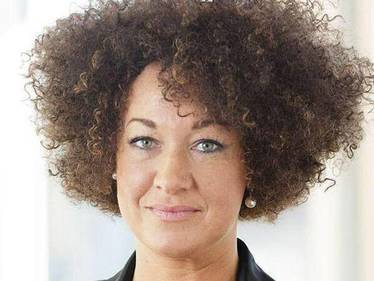

By: Jesus Radicals  I found out about Rachel Dolezal via an email with the subject line, “WTF”. I can’t remember everything that went through my mind as I followed the enclosed link article: to a story about a woman of predominantly European descent who masqueraded as a Black woman for a decade. But I am fairly certain my feelings were a mix of disbelief (Is this a joke?), confusion (Wait, what???), humor (#iggyonsteroids), and eventually anger. Anger at how long her charade went on. Anger at all the opportunities she received because of her pretense. Anger at the deception: the African American man she claimed as her dad; the adopted Black brother she said was her son; the suspicious reports about receiving hate mail; the false stories about growing up as a Black girl; the lies on social media about “going natural.” Anger that each position she had in the community and beyond, she occupied in place of Black women academics, activists and artists who struggle to get the access and recognition that our skills and knowledge deserve. That the Dolezal controversy came on the heels of Caitlyn Jenner’s emergence as a transgender woman made discussions about a complex situation even more complicated. As the hours passed, I steeled myself for the inevitable comparisons between the two stories. “Wait for it…Wait for it…Yep,” I thought as the transracial hashtag burst onto the scene. The only thing missing was a drumroll. From the beginning, the term transracial was deployed to invalidate transgender identities by nullifying Black women’s experiences. Comments along the lines of, “If Bruce Jenner can wake up one day and say he’s a woman, then why can’t Rachel Dolezal be Black?” were not about shaking off oppressive categories and ending identity policing, but instead were a one-two punch that sanctioned Dolezal’s cross-racial performance by maintaining a strict male-female binary. Although I was confident about the double negative implied in this discourse, I still struggled to know how to talk about something so nuanced in the midst of simplistic soundbites. It felt like trying to explain the difference between Twizzlers and tomatoes when everyone else is screaming, “Look! Food!”

As an intercultural competence and undoing racism coordinator, I knew I needed to equip myself to better understand and, if needed, respond to the issues of race, gender, privilege and identity that Dolezal had sparked. I knew that race is a social, political and historical construct that organizes superficial differences into hierarchies for the specific purpose of sustaining White power (particularly in the hands of the male heterosexual propertied sort). I knew that Blackness is not genetic or a costume one takes on and off at will, but instead is an identity that is forged in part by White supremacist imagination and the struggle against it. And although I didn’t have nearly the same understanding of transgender identity, I had learned enough to know that merely substituting racial terms and gender pronouns—as many folks were eager to do—did not reflect the intricacies of that experience. Believing that other undoing oppression workers might be similarly perplexed and in need of resources, I decided to look for articles on Dolezal and to post one a day on social media. I completed only four days before news broke of Dylan Roof’s shooting spree at Emmanuel AME Church. At that point, I gave up that project and focused my energies on Charleston, stopping only to cynically wonder just which racial box Dolezal would check off had she found herself staring down that barrel of hate. As I think about Dolezal in the shadow of ongoing White violence against people of color, a few things feel especially pronounced. For one thing, her kind of transracialism is a one way street. Donning blackface for ten years, though impressive on a number of levels, does not speak to what it is like to live as a person of color without a White identity to fall back on. That is, Dolezal, for all her dedication, could waive her Blackness at any point and that, in and of itself, makes her foray onto the dark side fundamentally different from those of us for whom there is no such recourse. When I walk through the streets of my city with Confederate flags waving in the wind and cops patrolling two and three cars deep, I am acutely aware that there is no mask I can put on or take off to prevent racially motivated threat or violence. The paper bag test legacy that worked in Dolezal’s favor has no inverse for people of color. Even if I straighten my hair, bleach my skin and wear blue-eyed contact lenses—as many brown-skinned people do worldwide—I would still be Black. This is made even clearer when we consider that even Black people with a parent of European descent are not afforded the luxury of Whiteness in the racial hierarchy. This situation is made possible because race is not about what someone feels inside or decides to call herself. It is also and perhaps primarily about how Whiteness categorizes us. It is also why undoing race and racism involves dismantling the systems that perpetuate the hierarchy. Individual race bending rooted in White hubris is not enough. Which brings me to another point. Whether Dolezal infiltrated the spaces she did to in solidarity with Black people or to gain access to spaces she coveted or some combination of the two is not the main issue. What she embodies is Whiteness’s insistence on prime access to all spaces, be it cultural terrain or actual landscape. Whether it is boohooing the social unacceptability of White people using the N-word (anymore) or demanding the right to keep a racist mascot as a sign of honor (despite indigenous peoples’ protests) or repackaging oneself as a Black woman (after suing your historically Black university for discriminating against you for being White), Whiteness demands the right to occupy any and every area it chooses. It does not accept limits. It cannot accept restrictions. It must be “Wherever. Whenever,” to quote the great Shakira. Dolezal’s action is beyond cultural appropriation: dabbling in others’ ethnic rituals and representation without accountability to those communities or any interest beyond the temporary gains such dabbling provides. It is colonizing. And it is lazy. At least that’s what I think. The resources that I collected and posted in my short-lived experiment, and which have helped shape the thoughts I offer here are listed below. They are accompanied by readings selected by Jesus Radicals co-organizers, Brett and Joanna. I am sure Brett and Joanna have reasons for the choices they made and their own motivations for finding those resources in response to Dolezal’s story. I speak only for myself in this introduction. In the closing moments of Spike Lee’s Bamboozled [spoiler alert], the police come after the Mau Maus, a group of Black power rappers who kidnap and murder a perceived rival. After unleashing a hail of bullets into the group, the police kill all but one person—a White member known as “One-Sixteenth Black”. One-Sixteenth was fully embraced by and in solidarity with his fellow Mau Maus. He believed in Black self-determination, used the same street language, rapped the same lyrics, spoke ill of the White man’s trickery and committed murder right alongside his comrades. He was, for all intents and purposes, a White-looking Black man at home among his crew. But when the cops show up with guns in tow, his life is the only one spared. Even when he begs the cops to kill him like his fellow Mau Maus, he can’t completely jettison his Whiteness or its privileges. Not through his heartfelt performance. Not while the game of racial roulette is in play. And the same thing goes for Rachel Dolezal. —Nekeisha Reading List: Vaneessa Vitiello Urquhart, "It Isn't Crazy to Compare Rachel Dolezal with Caitlyn Jenner, But They're Very Different," Slate, June 25, 2015. Jamelle Bouie, "Is Rachel Dolezal Black Just Because She Says She Is?" Slate, June 12, 2015. Meredith Talusan, "There is no comparison between transgender people and Rachel Dolezal," The Guardian, June 12, 2015. Zeba Blay, "Why Comparing Rachel Dolezal To Caitlyn Jenner Is Detrimental To Both Trans And Racial Progress," The Huffington Post, June 12, 2015. Yoni Applebaum, "Rachel Dolezal and the History of Passing for Black," The Atlantic, June 15, 2015. Rafi Dangelo, "Transgender vs. Transracial: Caitlyn Jenner & Rachel Dolezal," So Let's Talk About, June 12, 2015. Kat Blaque, "Why Rachel Dolezal Isn't Caitlyn Jenner" Kat Blaque Youtube Channel, June 14, 2015 Mia McKenzie, "The Rachel Dolezal Situation: Blackface, Appropriation, and Fuckery, Oh My!" Black Girl Dangerous, June 15, 2015.

Comments

|

Disclaimer

The viewpoints expressed in each reader-submitted article are the authors own, and not an “official Jesus Radicals” position. For more on our editorial policies, visit our submissions page. If you want to contact an author or you have questions, suggestions, or concerns, please contact us. CategoriesAll Accountability Advent Anarchism Animal Liberation Anthropocentrism Appropriation Biblical Exegesis Book Reviews Bread Capitalism Catholic Worker Christmas Civilization Community Complicity Confessing Cultural Hegemony Decolonization Direct Action Easter Economics Feminism Heteropatriarchy Immigration Imperialism Intersectionality Jesus Justice Lent Liberation Theology Love Mutual Liberation Nation-state Nonviolence Occupy Othering Pacifisim Peace Pedagogies Of Liberation Police Privilege Property Queer Racism Resistance Resurrection Sexuality Solidarity Speciesism Spiritual Practices Technology Temptation Veganism Violence War What We're Reading On . . . White Supremacy Zionism ContributorsNekeisha Alayna Alexis

Amaryah Armstrong Autumn Brown HH Brownsmith Jarrod Cochran Chelsea Collonge Keith Hebden Ric Hudgens Liza Minno Bloom Jocelyn Perry Eda Ruhiye Uca Joanna Shenk Nichola Torbett Mark VanSteenwyk Gregory Williams Archives

October 2017

|

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed