|

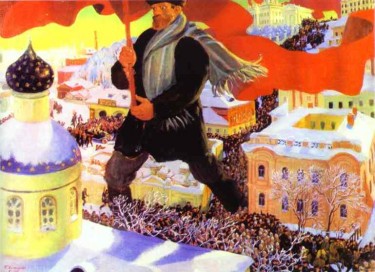

11/9/2010 Comments On Hope and AnarchismBy: Brenna Cussen Anglada  The epic movie “Reds” is based on the lives of the American socialist, journalist, and revolutionary Jack Reed (the only American to be buried at the Kremlin) and his wife and fellow writer, Louise Bryant. While the movie focuses heavily on the tumultuous and romantic relationship of the two characters, it also chronicles how Reed, along with his contemporary Emma Goldman, first ardently supported, and then became disillusioned by, the Bolshevist revolution in Russia. Watching the movie again last week, I was struck how this theme seems to play itself over and over in human history: passionate and well-meaning revolutionaries try to bring justice to the world—either through structural change, or violence, or both—but despite their best intentions, the institutions of power, in one form or another, ultimately prevail. Today there are social movements all around the globe attempting to bring about a better world—from voting in the “right” president or working through the international community, to blowing up buildings, buses, bridges, and dams or picking up arms and starting a rebellion. Behind all of these efforts exists compelling enthusiasm, righteousness, energy, and a willingness to sacrifice lives—both their own and others—for the sake of the cause. While I understand and often support the basic motivation of these activists (to ease suffering and restore justice) I find myself wary of the fundamental lack of hope their actions belie. Like for the characters in “Reds,” their admirable desire to create a perfect world eventually turns into desperation, because they believe that if they don’t do it, nobody will, and if justice is not achieved here on earth, it will never be achieved. While as a Christian, I of course desire to see justice attained here on earth, I ultimately have hope in a God who is the eternal giver of justice, a justice that is more loving and merciful and perfect than any human being could ever create. I write about this topic because I myself am often in danger of falling into the trap of believing the lie that through a life of anxious activism, I can fix the problems of violence, poverty, over-consumption, unfair prison systems . . .the list is long. I try to remind myself that while I am called by God to participate in His love through performing the works of mercy, it is participation, and not a control of outcomes, that God asks of me. Struggling to bring about a perfect world, while often stemming from the Christian motive of love for justice, can quickly turn into a lack of trust in our Creator. Pope Benedict XVI speaks to this phenomenon in his second encyclical Spe Salvi (Saved in Hope): “Our daily efforts in . . . working for the world’s future either tire us or turn into fanaticism, unless we are enlightened by the radiance for the great hope that cannot be destroyed even . . . by a breakdown in matters of historic importance. If we cannot hope for more than is effectively attainable at any given time, or more than is promised by political or economic authorities, our lives will soon be without hope.”(1) In the encyclical, Benedict addresses two movements in modern history, the French Revolution and the Bolshevist uprising, that both attempted to create “perfect” realities. Despite their seemingly different positions on the political spectrum—one was a revolution of the bourgeois, based on the “rule of reason and freedom,”(2) and the other of the proletariat, based on the idea of workers gaining control of the means of production—both movements had in common the belief that, through their own carefully planned action, they could hasten the coming of the “Kingdom of God,” whatever that kingdom meant to them. But neither movement wholly took into account the full personhood of every human being, forgetting that no matter what structures are put into place, free persons continue to be born into this world, and with each birth, the world, and hence the world’s structures, change. And as Pope Benedict reminds us, no matter how close to perfection those structures come in time, each person is created with free will, and this freedom, though it is a freedom to choose the good, “always remains also freedom for evil.” (3) In the late nineteenth century, the philosophy of personalism arose as an alternative to both the bourgeois and class-war mentalities. Personalism is the belief that every human being has inherent dignity by the very fact that each has been created in the image and likeness of God, and that all social structures, including governing bodies and economic systems, should only exist in order to allow the full dignity and freedom of every individual to flourish. Personalism is a form of anarchism, because it maintains that any government authority can never be dynamic enough—or personal enough—to take individual gifts and needs into account. Personalism is different than individualism, however, because personalism also recognizes that each human being operates within, and is responsible to, the community of which they are a part. Personalists believe that since salvation is communal, it is through the building up of the good of each human person that strong, healthy, and loving communities are built. And it is within such communities where hope for this world lies. One such advocate of personalist ideas was the co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, Peter Maurin, who agreed that one’s humanity could be best and fully expressed through the integration of one’s body, mind, and soul (especially in light of a modern society that tends to compartmentalize the three into school, exercise, and “Church on Sunday”). As an anarchist, Peter was skeptical of revolutionaries who called for forceful or coercive action to bring about change, and favored instead the creation of viable alternatives to the mainstream. He thus envisioned Catholic Worker farms as places where all three expressions of one’s humanity could be wholly employed through manual labor, study, and prayer. These farm communities, then, being comprised of persons making use of their full potential, would be then capable of living independently of government or corporate domination. They would cooperate with other communities, including houses of hospitality, where Christians could continue to practice the works of mercy, and strive toward building what he called “a new society within the shell of the old.” At New Hope Catholic Worker Farm, we are attempting to live in a community that recognizes the full dignity of each one of our members, and are working to expand that recognition in a practical way to every guest we encounter. As one experiment in this vein, we hosted in July our first week-long “agronomic university” session entitled, Growing Roots: The Catholic Worker in Thought and Practice. We invited twenty participants into our daily schedule of work and prayer, setting aside some of our usual work time for lecture and discussion. Unlike most conferences, where we sit for long hours and engage our intellect while our bodies are aching for sunlight and activity, the agronomic university allowed our minds to process our thoughts as our bodies were splitting wood, gardening, making yogurt, or walking in the woods identifying wild edible or medicinal plants. Rather than leaving anybody tired, the week’s physical and intellectual stimulation seemed to refresh fellow Catholic Workers for going back to their communities to continue their good work. A small start, perhaps, to the building up of strong, loving communities. At the same time, we at New Hope try bit by bit to be less reliant on governments or corporations for our daily needs—attempting to grow our own food without fertilizers or tilling, taking care of our own human waste, building economically cooperative relationships with our neighbors, etc. We have a long ways to go, but hope to continue to make progress. We realize we are only one in a long line of Christian communities that have experimented, and continue to experiment, with these ideas of personalism and Christianity in practice. This fact, too, gives me hope. Like Benedict, I believe that such communities serve as a testimony that hope in Christ is “not only a reality that we await, but a real presence.” (4) A closing thought: in the final pages of Spe Salvi, Benedict comments that because “no one and nothing” can answer for past centuries of suffering no matter what kind of beautiful world we may create in the future, then “there can be no justice without a resurrection of the dead.” And so as I sit here and write on the eve of the feasts of All Saints and All Souls, I am comforted to know that those dead who have gone before us, those who have struggled for justice and those who have been victims of injustice, are not in fact dead, but live on. Pie in the Sky by Peter Maurin Bourgeois capitalists don’t want their pie in the sky when they die. They want their pie here and now. To get their pie here and now bourgeois capitalists give us better and bigger commercial wars for the sake of markets and raw materials. But as Sherman says, “War is hell.” So we get hell here and now because bourgeois capitalists don’t want their pie in the sky when they die, but want their pie here and now. Bolshevist Socialists, like bourgeois capitalists, don’t want their pie in the sky when they die. They want their pie here and now. To get their pie here and now, Bolshevist Socialists give us better and bigger class wars for the sake of capturing the control of the means of production and distribution. But war is hell, whether it is a commercial war or a class war. So we get hell here and now because Bolshevist Socialists don’t want their pie in the sky when they die, but want their pie here and now. Bolshevist Socialists as well as bourgeois capitalists give us hell here and now without leaving us the hope of getting our pie in the sky when we die. We just get hell. Catholic Communionism leaves us the hope of getting our pie in the sky when we die without giving us hell here and now. (5) ------

Brenna Cussen Anglada lives on the New Hope Catholic Worker Farm and Agronomic University with her husband, Eric, and ten other community members. A Catholic and an anarchist, she finds a home in the Catholic Worker movement's emphases on hospitality, nonviolent activism, farming, and manual labor.

Comments

|

Disclaimer

The viewpoints expressed in each reader-submitted article are the authors own, and not an “official Jesus Radicals” position. For more on our editorial policies, visit our submissions page. If you want to contact an author or you have questions, suggestions, or concerns, please contact us. CategoriesAll Accountability Advent Anarchism Animal Liberation Anthropocentrism Appropriation Biblical Exegesis Book Reviews Bread Capitalism Catholic Worker Christmas Civilization Community Complicity Confessing Cultural Hegemony Decolonization Direct Action Easter Economics Feminism Heteropatriarchy Immigration Imperialism Intersectionality Jesus Justice Lent Liberation Theology Love Mutual Liberation Nation-state Nonviolence Occupy Othering Pacifisim Peace Pedagogies Of Liberation Police Privilege Property Queer Racism Resistance Resurrection Sexuality Solidarity Speciesism Spiritual Practices Technology Temptation Veganism Violence War What We're Reading On . . . White Supremacy Zionism ContributorsNekeisha Alayna Alexis

Amaryah Armstrong Autumn Brown HH Brownsmith Jarrod Cochran Chelsea Collonge Keith Hebden Ric Hudgens Liza Minno Bloom Jocelyn Perry Eda Ruhiye Uca Joanna Shenk Nichola Torbett Mark VanSteenwyk Gregory Williams Archives

October 2017

|

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed