|

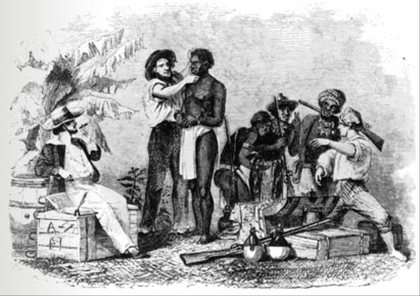

By: Joshua Kercsmar  As a historian who studies slavery and agriculture, I’m interested in probing the mutual oppression of humans and animals. Doing so has potential to offer new ways of understanding the past, and also to help us think more deeply about justice for humans and animals in the present. Toward that end, my current book project traces how the treatment of animals and slaves intersected on plantations in Virginia, South Carolina, and the Caribbean during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. We might think of the 1600s and 1700s as the beginning of modern industrial farming. This was a period that saw rapid modernization in many realms of agriculture, from crop rotations, to processing technologies, to animal breeding. Planters in North America and the Caribbean, who often grew crops like tobacco, rice, and sugar, and who needed livestock and slaves to keep their enterprises going, were caught up in these transformations. While they didn’t always or everywhere adopt new agricultural methods, they did so enough of the time to allow us to test whether agricultural modernization influenced planters’ treatment of animals and slaves. Thomas Thistlewood, who worked as overseer on a 1,500-acre plantation in Jamaica, offers a good case study. In many ways Thistlewood was typical of planters in Jamaica at this time. An Englishman, he came to the island hoping to make his fortune in the lucrative sugar industry. He raised livestock, and eventually owned slaves whom he put to work on a small plantation that he bought for his own use. Thistlewood was atypical, however, in that he kept detailed journals of his thoughts and activities between 1748 and 1786, a record that runs to more than 10,000 manuscript pages. In reading these journals, it is clear that Thistlewood participated in a system that valued labor efficiency above all. To read Thistlewood’s journal is to realize that he viewed his plantation as a machine. Land, livestock, and slave labor made up the main components, and being profitable meant finding ways to squeeze the maximum output from each component. It is also to realize, however, that Thistlewood did not always get what he wanted from his laborers. By paying attention to these dynamics, we learn much about how the treatment of humans and livestock intersected on a typical Jamaican plantation. Thistlewood had been a livestock trader before getting into the sugar business. While his entries on buying and selling animals tend to be terse, it is clear that his main concern was to extract maximum production from them in the form of meat (which he could sell at market), manure (which he could use as fertilizer), and muscle (which he could use to pull his perennially malfunctioning sugar-grinding mill). Yet one of the main obstacles to his doing any of this was that Jamaica’s hot climate, coupled with brutal work regimes, killed animals with astonishing speed. Mules on sugar plantations lived only six to eight years on average, and oxen four to six⎯less than half their potential lifespans.1 Given the difficulty of keeping livestock alive, it was important to buy strong, hardy animals, free from deformities or injuries. As with livestock, Thistlewood learned to appraise slaves’ value according to their physical makeup. After spending more than a quarter century in Jamaica, he offered this advice to buyers in the market for slaves: I would Choose men Boys, and girls, none exceeding 16 or 18 years old, as full grown Man or Woman Seldom turn out Well, and beside they shave the Men So Close & glass them over So much, that a person Cannot be Certain he does not buy old Negroes . . . Those negroes that have big Bellies, ill Shaped Legs & great feet, are Comonly dull and Sluggish, & not often good, whereas those Who have a good Calff to their Legg and a Small or Maderate Sized Foot, are Commonly Nimble, Active Negroes. Many Negroe Men are bursten [herniated] and are always the Worse for it, therefor one Would not buy them if perceptable, have also observed that many New Negroes, who are bought Fatt and Sleek from a board the Ship, Soon fall away such in a plantation, Whereas those which are Commonly hardier. Those whose Lips are pale, or Whites off their Eyes yellowish, Seldom healthfull.2 How Thistlewood thought about and treated slaves is also telling. That he and other planters often used overlapping names for Africans and livestock, but not for Africans and whites, suggests that they participated in an emerging scientific racism that posited categories of essential difference between whites and blacks.3 Those who delineated these categories often drew explicit comparisons between blacks and animals, as Thistlewood himself was willing to do. “As a Mule has not the feeling of a Horse,” he wrote, “So . . . a negroe has not the Perfection of feeling equal to White People.” To corroborate his claim Thistlewood repeated the observation of his boss, William Dorill, who “himself has Seen them have their Limbs Cut off, and never Shrink.”4 This notion that Africans could barely feel pain not only made it easier to equate them with livestock (which were supposedly insensitive to pain as well), but also served to justify Thistlewood in his use of terror and violence to make slaves do his bidding. As one encounters reference after casual reference to Thistlewood flogging, branding, and raping his slaves, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that much of it was strategic. That is, while Thistlewood sometimes practiced outright sadism, he clearly thought that the only way to get maximum production from his slaves was to punish them according to their personalities and intentions. While we cannot necessarily draw a direct connection to Thistlewood’s Jamaican context, it is worth noting that contemporary manuals on horsemanship often spoke of the need to understand the personality of one’s horse in order to know how to manage and discipline the animal. One might think that Thistlewood’s use of brutality to correct slaves’ wayward habits mirrored his similar treatment of animals. But in fact things were not so simple. Thistlewood cared deeply about the welfare of his livestock because, as with slaves, he wanted to profit from them. But Thistlewood often did not have direct charge over his animals. In each place that he lived slaves were the ones who saw to animals’ proper feeding and care, which often put them in a position where they had to place the welfare of Thistlewood’s animals above that of their own. Predictably, this conflict of interest bred resentment and sabotage. Thistlewood often complained about slaves who deliberately injured or killed his animals. His anxiety led him to punish slaves whom he suspected of harming his animals, as when he “flogged Strap” for allegedly “stabbing Mackey,” one of Thistlewood’s favorite riding horses.5 In so doing, Thistlewood may have deterred slaves from hurting his animals in the short term. But in the long term, he only fueled a dysfunctional system in which physical distance from his animals led him to rely on slaves, whose violence toward animals led to whippings, which in turn increased slaves’ resentment toward Thistlewood and made them more likely to harm his animals. In the end, everyone suffered: Thistlewood, slaves, and livestock. Where Thistlewood explicitly conflated animals and slaves was in his accounts of their deaths. In particular, he used his diaries as account books in which he monetized human and animal lives, often making little or no distinction between the two. For example in mid-August of 1773, a particularly bad month, Thistlewood recorded: Within this month past, have lost as follows: By this point, Thistlewood had become accustomed to Jamaica’s high mortality rates. In May 1751, shortly after his arrival, he had been shocked at both the casual treatment of death on the island and the fact that a slave burial resembled that of an animal: “In the afternoon Mimber, a Fine Negro Woman, [was] buried today . . . like a Dog! She died yesterday.”7 By 1773, though, having seen the deaths of untold numbers of animals through overwork and disease, and having experienced the continual need to replace dead slaves with living ones, he accounted the deaths of animals and slaves as mere monetary losses that could (presumably) be reversed by purchasing more. In this very practical sense, as well as through how he accounted for them, animals and slaves were interchangeable: both were units of production in the larger plantation enterprise, essential to its functioning but at the same time replaceable. If we trace the history of animal management from the early modern period forward, we notice that concerns with animal welfare played a very minor role. From the growth of slaughterhouses beginning in the early nineteenth century, to the development of industrial fishing beginning in the late nineteenth, to the rise of industrial agriculture post-WWII, humans usually treated livestock not as individuals, but as inputs into an ever-expanding commercial production machine. In The Jungle (1906), Upton Sinclair described the “high squeals and low squeals, grunts, and wails of agony” that filled Chicago slaughterhouses. The pig’s “wishes, his feelings,” Sinclair wrote, “had simply no existence at all; [the machine] cut his throat and watched him gasp out his life.” Sinclair’s novel also pointed to another important fact. The vast majority of those who worked in slaughterhouses were (and are) poor immigrants who had little choice but to take what work they could find, regardless of how dirty, dangerous, or uncivilized. Indeed, one of reasons why reformers wanted to build slaughterhouses in the early nineteenth century was that killing animals came to be seen as gross and uncivilized, an operation better done behind walls than in the open farmyard. Yet it’s precisely in distancing ourselves from industrial slaughter that we give ourselves permission to ignore the exploitation that makes it possible.8 It’s true that modern slaughterhouses differ in many respects from slave plantations. Unlike slaves, for example, slaughterhouse workers receive wages, and can quit if they want to (which they do quite regularly, as the annual turnover rate in the U.S. slaughter industry exceeds 100 percent). But we should recognize that on plantations and the floors of meat factories alike, workers and animals often experience mutual oppression through precisely the same mechanisms: a rationalized pursuit of profit, coupled with social and geographic distance between managers and workers, suppliers and consumers. Allowing ourselves to see these parallels may not be pleasant. But doing so is necessary if we hope to address how human and natural exploitation go hand-in-hand. Notes:

Joshua Kercsmar is currently a Lilly Postdoctoral Fellow in the Arts and Humanities at Valparaiso University. His teaching interests span early America, environmental history, the history of slavery, religious history, and human-animal interactions. His current research examines the mutual oppression of animals and slaves in early America, and considers how and why Protestants challenged and supported that oppression. He is revising a book manuscript, tentatively titled Animal Husbandry and the Origins of American Slavery, which traces how British efforts to raise five species—cows, sheep, pigs, horses, and dogs—served as a model for enslaving humans in America between 1550 and 1815. Joshua is married and has two young children—a son and a daughter. He enjoys reading, being outdoors, playing guitar, taking down opponents in ping-pong, and hanging out with his family.

Comments

|

Disclaimer

The viewpoints expressed in each reader-submitted article are the authors own, and not an “official Jesus Radicals” position. For more on our editorial policies, visit our submissions page. If you want to contact an author or you have questions, suggestions, or concerns, please contact us. CategoriesAll Accountability Advent Anarchism Animal Liberation Anthropocentrism Appropriation Biblical Exegesis Book Reviews Bread Capitalism Catholic Worker Christmas Civilization Community Complicity Confessing Cultural Hegemony Decolonization Direct Action Easter Economics Feminism Heteropatriarchy Immigration Imperialism Intersectionality Jesus Justice Lent Liberation Theology Love Mutual Liberation Nation-state Nonviolence Occupy Othering Pacifisim Peace Pedagogies Of Liberation Police Privilege Property Queer Racism Resistance Resurrection Sexuality Solidarity Speciesism Spiritual Practices Technology Temptation Veganism Violence War What We're Reading On . . . White Supremacy Zionism ContributorsNekeisha Alayna Alexis

Amaryah Armstrong Autumn Brown HH Brownsmith Jarrod Cochran Chelsea Collonge Keith Hebden Ric Hudgens Liza Minno Bloom Jocelyn Perry Eda Ruhiye Uca Joanna Shenk Nichola Torbett Mark VanSteenwyk Gregory Williams Archives

October 2017

|

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed