|

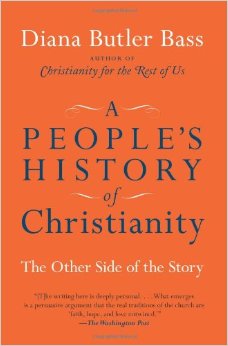

By: Michael Iafrate  The title of Diana Butler Bass’ new book, A People’s History of Christianity, immediately grabbed my attention, as I am a pretty big fan of Howard Zinn. Indeed, Bass’ book is billed as an attempt to write church history “in the same spirit” as Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. With this kind of title and marketing strategy, Bass is likely to attract a lot of readers. The difficult part, though, of modeling a book after such a classic work is that readers and reviewers have no choice but to evaluate the book in light of the original. More specifically, Bass intends to respond to our “posttraditional” situation in which different factions of the church each suffer from their own brand of collective amnesia: conservatives have forgotten the ethical impulse of historic Christianity and progressives/liberals have forgotten the devotional roots of that ethical impulse. Each chapter, then, strives to highlight the devotional and ethical practices of various moments in the church’s history through the narration of the “subversive” and “alternative” stories of ordinary Christians, sidestepping the usual account of “Big-C” Christian history (“Christ, Constantine, Christendom, Calvin and Christian America”) in favor of a more radical, socially engaged story of what Bass calls “generative Christianity.” If this sounds like a big job, it is. Zinn needed close to 700 pages to cover the 200 year history of the united states. The identically-titled scholarly version of A People’s History of Christianity, edited by Richard Horsley, spans seven volumes. That Bass squeezed her people’s history into 300 pages of 13-point font type made me a little skeptical of how much it could possibly cover. Indeed, choices had to be made and Bass admits in the introduction that she found it necessary to exclude significant areas of church history. In fact, she opted to focus on Western Christianity as the “spine of the story” she wants to tell, in order “to help Western Christians move away from their triumphal Big-C history to a more humble reading of their story” (17). I’m not sure why it didn’t seem to occur to Bass that what Western Christians really need in order to be more humble is exposure to the richness and challenges of non-Western Christianity. In addition to being oriented to the Western church, Bass neglects the parts of the Western church in the South: Oscar Romero gets half a sentence; so does Latin American liberation theology. Beyond that, there are few examples of “radical” expressions of Christianity outside of Europe and the united states. These deliberate omissions seem to be quite the wrong choice to make in light of what she wants to do in the book. Don’t get me wrong: I think it’s entirely possible to write a “people’s history” of the (North-) Western church alone. But in doing so, one can’t ignore the relationship to the rest of the church, glossing over the ugly history of the Western church and apologizing for it merely by saying she does not mean “to exclude anyone’s story or hurt anyone’s feelings” (17). The result of Bass’ methodological option is a narrative relating the pleasant parts of Western Christian history, a telling of the stories of individuals who “got it right” in living out the Christian life of charity, justice, and peace. It is an informative read, no doubt, and recovers some figures who are not usually mentioned in the standard Christian history books. But in reading the book, you get the distinct feeling that there is yet another side to this supposedly “other” side of the story. In order to be truthful as a Christian historian, in order to truly tell “the other side of the story,” a deeper methodological and ethical option must be made. Howard Zinn made this deeper option and it is what made his book so profound and such a classic model for anyone doing scholarship from and for the underside of history. Zinn’s book was important not because he recovered stories of “great Americans” who happened to “get it right,” embodying whatever it is that is good in the narratives, myths and ideals of the united states of america. No, Zinn’s book was a “people’s history” because he told the story of the u.s. from the perspective of those marginalized citizens of the united states as well as those who were america’s victims. When Zinn did related stories of those americans who “got it right,” those stories were never divorced from the stories of the victims whose voices were heard throughout the narrative. In other words, Zinn’s book wasn’t intended to make americans feel better about themselves. It was to tell americans the truth about themselves, including the truth that things don’t have to be this way. Unfortunately, for all the authorial intent to inspire a “progressive” Christianity of peace and justice, the gigantic hole left in the text—the absence of those on the underside of Christian history—left me feeling that the author simply wanted me to feel better about the fact that I am a Christian. Perhaps that is what some readers might need on whatever leg of the journey they find themselves, but in my opinion, the Christian history I find “inspiring” is Christian history that is truthful and in which no one is left out. I’ll be brief in describing two additional criticisms. First, the book’s tone seems to suffer from what I would call an anti-institutional and anti-hierarchical bias. The book’s jacket states that A People’s History “authenticates the vital, emerging Christian movements of our time” over and against “the triumph of orthodox doctrine imposed through power and hierarchy.” I couldn’t help but feel that the evil “institutional church” looming in the background was the Roman Catholic Church, as many of the heroes cited are individuals who stood up to the abuse of power in the Catholic Church. While I certainly can sympathize with a suspicion of hierarchies and I appreciate the attention to the misuse of power and authority in the Catholic Church, I think some balance is called for as well as a recognition of the ambiguities of both the institutional church as well as the countless “emerging” movements that have irrupted throughout Christian history. My final criticism is stylistic. Bass includes contemporary stories throughout the book which illustrate the relevance of each historical figure or movement she is about to discuss. These asides are well done and Bass draws very good connections between the historical episodes and the way historic debates, struggles, and ideas “repeat themselves” in our own times. But Bass includes one of these contemporary illustrations not only at the beginning of every chapter, but at the beginning of every section of every chapter. As good as these pieces are, I found that they broke up the narrative and ultimately became a distraction. Aside from these important critiques, the book reads beautifully. The writing is very good and the chosen stories and individuals are indeed inspiring in many ways (her account of St. John Chrysostom’s life and work is one example), as is her ultimate message: “You have studied church history. Now it is your turn. Go make church history” (310). The book certainly represents an alternative to triumphalistic versions of the church’s presence in the world, highlighting several key saintly individuals who “got it.” But judged by the standard of Zinn’s historical method and radical ethical option, those looking for a real “people’s history”—the other side of the story—will have to look elsewhere.

Comments

|

Disclaimer

The viewpoints expressed in each reader-submitted article are the authors own, and not an “official Jesus Radicals” position. For more on our editorial policies, visit our submissions page. If you want to contact an author or you have questions, suggestions, or concerns, please contact us. CategoriesAll Accountability Advent Anarchism Animal Liberation Anthropocentrism Appropriation Biblical Exegesis Book Reviews Bread Capitalism Catholic Worker Christmas Civilization Community Complicity Confessing Cultural Hegemony Decolonization Direct Action Easter Economics Feminism Heteropatriarchy Immigration Imperialism Intersectionality Jesus Justice Lent Liberation Theology Love Mutual Liberation Nation-state Nonviolence Occupy Othering Pacifisim Peace Pedagogies Of Liberation Police Privilege Property Queer Racism Resistance Resurrection Sexuality Solidarity Speciesism Spiritual Practices Technology Temptation Veganism Violence War What We're Reading On . . . White Supremacy Zionism ContributorsNekeisha Alayna Alexis

Amaryah Armstrong Autumn Brown HH Brownsmith Jarrod Cochran Chelsea Collonge Keith Hebden Ric Hudgens Liza Minno Bloom Jocelyn Perry Eda Ruhiye Uca Joanna Shenk Nichola Torbett Mark VanSteenwyk Gregory Williams Archives

October 2017

|

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed