|

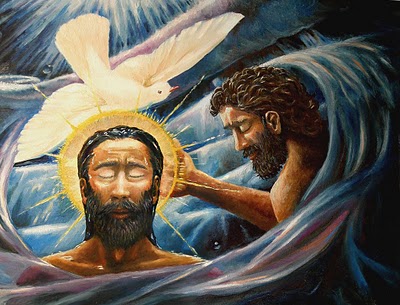

4/20/2017 Comments Convincing Christians: On the Work of Animal Liberation in the Name of Jesus—a Reply to Socha and TaylorBy: Nekeisha Alayna Alexis Editor's Note: This article was originally published at Animal Liberation Currents. I said in my heart with regard to human beings that God is testing them to show that they are but animals. For the fate of humans and the fate of animals is the same; as one dies, so dies the other. They all have the same breath, and humans have no advantage over the animals; for all is vanity. All go to one place; all are from the dust, and all turn to dust again. Who knows whether the human spirit goes upward and the spirit of animals goes downward to the earth? 1  Baptism of Christ: Jesus is baptized in the Jordan River by John. By Dave Zelenka Baptism of Christ: Jesus is baptized in the Jordan River by John. By Dave Zelenka I do not remember how I first came across Ecclesiastes 3:18-21. What I do recall is that I found the passage unexpectedly and I loved it immediately. The poetic text, which trespasses against the human-animal binary, resonated with my perspectives as a vegan, animal liberationist, critical animal scholar, and Christian immersed in Anabaptist theology and ethics and influenced by anarchist politics. Now one of my favorite verses, it is one part of the theological groundwork that informs my spiritual, intellectual and emotional commitment to shalom2 with all God’s creatures. That Ecclesiastes 3:18-21 seemed to pop out of nowhere — that I never heard it preached in a sermon or during Sunday School — testifies to the church’s widespread inattentiveness to other animals and our shallow knowledge of the Bible in general. Even when Christians do notice texts like these, we tend still to distort their meaning. As Rachel Muers notes, Ecclesiastes 21 “has been read as emphasizing the difference between humanity and ‘the beasts that perish.’ In context, however, it makes more sense as a reminder of how questionable the dividing line is between us and the ‘beasts.’”3 An extensive, scholarly examination of Scripture as well as church history, hymnody and other Christian artifacts reveals that mutuality, sameness and interconnectedness between humans and other animals are strong vibrant themes within the faith. Indeed, these themes are more prevalent than our contemporary readings allow us to see, shaped as we are by legacies of the Enlightenment and industrial revolution, by antiquated ideas about human and animal biology, and by anthropocentric philosophies and technologies. Since becoming vegan, a journey that began and crystallized while I attended seminary, I have become increasingly aware of biblical texts and trajectories that decenter humanity and undermine support for dominating other animal persons. These alternative streams interrupt the prevailing narratives of God-ordained exploitation that comprise so much of Christian discourse, practice and belief. Yet they usually go unnoticed, not only by Jesus followers but by our critics as well. It is because I know how Christian theology and ethics can benefit other animals that the question of why more of us are not vegan is compelling to me. It is also because I am painfully aware of how mainstream Christianity justifies terror against other creatures — in addition to its already devastating record of colonialism, enslavement and ongoing conquest — that identifying the obstacles and finding meaningful solutions is so urgent. As Kim Socha and Rowan Taylor point out, “Most of the 90 billion animals slaughtered in the US every year . . . suffer and die at Christian hands on their way to Christian stomachs . . . and relatively few Christians seem to care.”4 That enormous number does not even include all the animals Christians skin alive, hunt, experiment on and abuse while other Christians stand by or bless the suffering outright. These grave circumstances call for careful analysis of why so many Christians forgo veganism and reject animal liberation, and thoughtful strategies to overcome their resistance. So color me confused when Socha and Taylor offer the opposite in their writing on the issue. In “Why Are so Few Christians Vegan?” Socha and Taylor’s arguments begin reasonably enough. Writing in response to theologian Charles Camosy’s article, “Why All Christians Should go Vegan,” they rightly name the shortcomings of the Pope’s recent statements about other animals and criticize animal advocates for accepting such moderate pronouncements as signs of great progress. They also take issue with theologian Camosy for featuring evangelical leader Franklin Graham in his article argument for biblically mandated veganism. Each of these critiques makes sense, but especially when it comes to Graham. Graham is racist, heterosexist, xenophobic, Islamophobic and compromised by an idolatrous allegiance to American nationalism. Even if he stops eating other animals, it also matters that his politics and hateful and inflammatory, making Camosy’s mention of him perplexing and misguided. By calling out the Pope, Graham and Camosy, Socha and Taylor helpfully emphasize the difference between veganism rooted in antispeciesist and intersectional concern for other animals and plant-based eating that does not disturb the hierarchies of human and nonhuman animal oppression. Unfortunately, their incisive look into the limitations of veganism as practiced by the likes of Graham dissipates when they challenge Christianity’s ability to be compassionate toward other animals as a whole. The trouble begins when the authors present research to demonstrate Christianity’s incompatibility with veganism. Citing one study and two Internet surveys in which few Christians say they are vegan, especially as compared to atheists, agnostics and others, Socha and Taylor make the sweeping assertion that Christianity itself is the problem. “It’s as if Christian belief actually suppresses veganism,” they write, “perhaps because . . . human exceptionalism inhibits believers from empathizing with other animals.” This is an altogether baffling interpretation of the results. The problem could just as easily be that few Christians visit the Vegan Truth website and never saw the survey or perhaps that the parameters of the Humane League Lab’s study excluded a number of Christians. The problem could also lie in the fact that many Christians, like people from other religious or non-religious backgrounds, believe humans need to eat animal flesh for good health. But for Socha and Taylor, the data is enough to prove that Christianity — in all of its expressions across the last 2,000 years — can do little, if anything, to inspire empathy for other animals. And, by the way, it’s all the Bible’s fault. What follows in the wake of this assumption are a series of arguments that betray how little Socha and Taylor know the water they are wading in. The topic of dominion, which many biblical scholars and linguists have already tackled, makes a speedy appearance before the authors employ the same cherry-picking approach to Scripture that they pan Camosy and other Christians for employing. Engagement with the growing number of theologians, ethicists, historians and biblical scholars who are making innovative strides within the tradition for the sake of other animals — thinkers that are readily accessible to anyone interested enough to find them — is woefully absent in favor of sarcastic asides and true but tangential comments about Donald Trump. Indeed, their article has no citations from any biblical scholars or theologians of any caliber, nor any sustained engagement with the textual or historical contexts of the passages about which they write. Socha and Taylor’s reflection is an excellent example of a classic mistake that persists inside and outside Christian circles with disastrous results: that we can simply pick up the Bible, read it in English or another translation, grasp its full meaning and apply it wholesale to whatever subject. The social and political settings that shaped various books of the Bible, the languages in which they were written, the cultures to which the early Israelites and followers of The Way are responding — all of these pieces are important for determining the meaning of biblical texts. As someone who is not a biblical scholar and who does not know ancient Hebrew or Greek or other helpful languages like Syriac or Aramaic, I am fully aware of the need to call in reinforcements when thinking critically about Scripture, especially when I am arguing for the beloved personhood of other animals and Christian responsibilities to them. Animals and the Strange World of the Bible Instead of responding verse for verse to Socha and Taylor’s biblical interpretations — all of which other Christian scholars have already addressed5 — I want to take the conversation in more creative and constructive directions. To accomplish this, I will rely heavily on an example from biblical scholar and theologian Richard Bauckham. In his essay, “Jesus and the Wild Animals (Mark 1:13): A Christological Image for an Ecological Age,” Bauckham takes an entire chapter to examine a single verse from one of the gospels. Yet his work on this text shows how critical biblical study, though an involved exercise, can disturb Christianity’s standard approaches to other animals. The verse, coupled with verse 12, reads: At once the Spirit sent him out into the wilderness, and he was in the wilderness forty days, being tempted by Satan. He was with the wild animals, and angels attended him. The two lines, which are sandwiched between the account of Jesus’ momentous baptism and Jesus announcing the good news and gathering his disciples, seem relatively inconsequential. Except, as Bauckham reveals, something truly groundbreaking is happening here: something that is not transparent by reading the translated text alone. The significance of the brief passage hinges on the Greek words translated as “was with the wild animals.” This phrase is not just a statement about proximity. Instead, “Mark portrays Jesus in peaceable companionship with animals which were habitually perceived as inimical and threatening to humans.” Although understanding “with” as being in “peaceable companionship” adds an interesting layer to the verse, the magnitude of the message is entirely lost without knowing the ancient Jewish tradition’s worldview on humans and undomesticated animals. Frist, they viewed wild animals as “threats to humanity,”6 including people, their domesticated animals and their cultivated land, and “the world as conflict between the human world and wild nature.”7 However, they also saw this state of hostility as antithetical to the order of God and had expectations for how that hostility would end. I do not have space to summarize all of Bauckham’s elegant and in-depth exegesis here. However, his conclusion is worth quoting at length. He writes: Mark’s simple phrase . . . indicating a peaceable companionship with the animals, contrasts with the way the restoration of the proper human relationship to wild animals is often portrayed in Jewish literature. The animals are not said to fear him, submit to him, or serve him. The concept of human dominion over the animals as well as domination for human benefit is entirely absent. The animals are treated neither as subjects nor as domestic servants. . . . Jesus does not terrorize or dominate the wild animals, he does not domesticate them, nor does he even make pets of them. He is simply ‘with them.’ . . . For us Jesus’ companionable presence with the wild animals affirms their independent value for themselves and for God. He does not adopt them into the human world, but lets them be themselves in peace, leaving them in the wilderness, affirming them as creatures who share the world with us in the community of God’s creation.8 In Mark, Jesus’s first act after baptism is not ministry among human beings, but overcoming the division between human and wild animal creatures. This restoration is part of how Mark identifies Jesus as the Offspring of God and it has deep implications for those who confess Jesus to be more than a guru or prophet. None of this meaning is readily apparent to the ordinary reader but it is there and waiting to be leveraged in service of veganism and animal liberation more broadly. Alongside biblical scholarship is the theological work of reimagining core Christian concepts with animals at the center. In my own research, I’ve begun to pursue questions that invite an entirely new course. If we take seriously, for example, that God incarnates (becomes flesh9), not only as a human animal in Jesus but also descend as a bird, we might also reimagine the place of other animals in the divine character of God (Trinity). If we take seriously that Jesus is the end of all sacrifice (Hebrews 10), then our concept of salvation include other animals and how might liberation for other animals shape our meaning of salvation? Like Camosy’s article on Genesis, none of these theological and biblical re-framings by itself is likely to overturn centuries of ruinous thought and practice. But, held together with the many other counter-narratives within Scripture, they can form a distinctly Christian rejection of the interspecies violence to which Socha, Taylor and I are all opposed. To convince or not to convince In their conclusion, Socha and Taylor offer the following counsel to animal advocates: It is far better to bypass the theology altogether and appeal directly to Christian hearts rather than heads. After all, Christians are human too, with the same capacities for empathy and compassion that drive non-Christians to be vegans. Showing the brutality and suffering that goes into their daily lifestyle choices might have more impact than a carefully crafted sermon. Frankly, this advice is absurd. First, theology is a matter of the head and the heart, so it is important to appeal to both ways of knowing in any argument, including ones related to animals. Second, many an animal advocate can testify to the hit or miss effectiveness of cruelty narratives. The very same person who became vegan after watching uncover footage at the slaughterhouse may easily “fall off the wagon” at the smell of grandma’s turkey or the sight of a McDonald’s. I have learned that it is necessary to speak to Christians, not only in light of social justice, ecological care or animal suffering, but also from the place of our faith commitments. Cognitive shifts are essential to changes in behavior, and for many Christians reinterpreting Scripture and reframing theology is key to that process. Socha and Taylor’s recommendation also fails to account for Christianity’s rapid rise in the global south. With that view in mind, the authors risk being ethnocentric by associating all of Christianity with car purchases, air conditioning and lawn mowing. As Christianity shifts quadrants, a blanket dismissal of the faith as inherently and irretrievably opposed to aiding other animals — aside from being false — has problematic implications in terms of race, class and nationality, to say the least. With Western ways of breeding, rearing and consuming other animals spreading rapidly, animal advocates may need to consider fresh and authentic ways to enter theological and biblical debate. Taking this step does not have to involve learning ancient biblical languages or going to seminary. It does not mean that atheists, agnostics or liberationists of other faiths have to become Christian or think our beliefs are logical. It certainly does not mean supporting the likes of Steve Bannon and Franklin Graham. The strategy is as simple as becoming familiar with a handful of arguments, scholars and resources to which you can point Christians you encounter. I have contributed to at least one series designed specifically for this purpose.10 In my experience, the deterrents to becoming vegan among Christians is very often the same for people from other backgrounds. Many people are still unaware of the horrors that are happening within animal agriculture. Others who know the suffering are not sure how to make the transition. Others still are worried about how they will continue relating to family and friends. Health questions and refrains about human evolution are part of the equation. These concerns multiply for those surrounded by status quo readings of the Bible. But “Christianity” is not the sole culprit and these obstacles can be overcome from within the tradition. Promoting veganism and animal liberation in terms that are meaningful to Christians is a pressing task. Failure to do so is not only a choice: it is an unnecessary decision that abandons other animals. Jesus-followers are treading new paths and the possibilities are exciting. May there be more collaboration across our religious divide: not less. Notes:

Nekeisha is the co-founder of Jesus Radicals and co-organizer of its annual anarchism and Christianity conference. She is an occasional writer and speaker with numerous interests including animal ethics from a Christian and anti-oppression perspective. She joined the Anabaptist/Mennonite tribe in 2003 and works for anti-racist transformation within the church. She also takes part in ecumenical conversations as part of the Ekklesia Project.

Comments

|

Disclaimer

The viewpoints expressed in each reader-submitted article are the authors own, and not an “official Jesus Radicals” position. For more on our editorial policies, visit our submissions page. If you want to contact an author or you have questions, suggestions, or concerns, please contact us. CategoriesAll Accountability Advent Anarchism Animal Liberation Anthropocentrism Appropriation Biblical Exegesis Book Reviews Bread Capitalism Catholic Worker Christmas Civilization Community Complicity Confessing Cultural Hegemony Decolonization Direct Action Easter Economics Feminism Heteropatriarchy Immigration Imperialism Intersectionality Jesus Justice Lent Liberation Theology Love Mutual Liberation Nation-state Nonviolence Occupy Othering Pacifisim Peace Pedagogies Of Liberation Police Privilege Property Queer Racism Resistance Resurrection Sexuality Solidarity Speciesism Spiritual Practices Technology Temptation Veganism Violence War What We're Reading On . . . White Supremacy Zionism ContributorsNekeisha Alayna Alexis

Amaryah Armstrong Autumn Brown HH Brownsmith Jarrod Cochran Chelsea Collonge Keith Hebden Ric Hudgens Liza Minno Bloom Jocelyn Perry Eda Ruhiye Uca Joanna Shenk Nichola Torbett Mark VanSteenwyk Gregory Williams Archives

October 2017

|

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed